If there's one thing about my childhood that, in retrospect, makes me wonder if I actually grew up in a 50's coming-of-age movie instead of a small lake town in the late 80's, it's my earliest memories of buying comic books. Both of the following points are true:

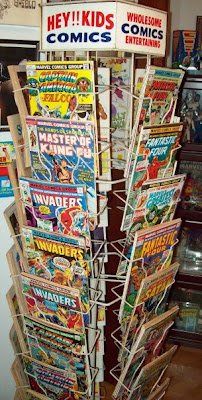

1) I bought my first comics from a wire spinner rack in a general store that also sold live worms, nightcrawlers, and other fish bait.

2) Those comics had ads that you could clip out and drop in an envelope, along with 50 cents, to mail away for X-ray glasses, sea monkeys, and glow-in-the-dark shoelaces.

Just thinking about it makes me hear Daniel Stern in my head, narrating my pre-adolescence while time plays out like a Country Time Lemonade commercial. How in the hell could you ever buy a comic book outside a comic book store? How did any mail-order company on the planet ever make all its money off spare change from ten-year old boys? Why on earth did my parents let me order weird crap from those places? Weren't they worried about Terrorism??

It's friggin weird when you're 33 years old and you can already look back on your youth and remember it as "a more innocent time," but seen through the frame of buying comics, I guess that's kind of what it was. Not that the comics I bought were in any way timeless -- my favorite books were He-Man, ALF (yep), The Adventures of Bayou Billy (uh huh), and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles Adventures (the Archie-published spinoff from the cartoon show). The decade-specific nature of these comics reflected the discerning taste of any ten-year-old worth his weight in Garbage Pail Kids cards -- I had no sense of what was "supposed" to be good; I just knew what I thought was awesome.

TMNT is the only one of those early franchises that has managed to hang on as a pop culture staple (but to be fair, as a youth I wouldn't know about its origins as a legit indie comic series for years to come.) Even then, the ads in a typical Ninja Turtles comic seemed to speak of deeper worlds than I could fathom -- the Eastman & Laird art that was used in advertising most TMNT products was considerably more dark and gritty than the goofy cartoons dominating my world at that age.

TMNT was one of my first forays into the idea that the fantasy and sci-fi stories I loved could also be kind of...scary. Moody. Mysterious. Weird. And hand in hand with that dim understanding was my curiosity about roleplaying games.

There were no rules in my house about not playing RPGs, but the fact remained that I didn't know anyone who played them. A couple of my friends had creepy older brothers who offered to show us how to play D&D, but the prospect of hanging out with older kids was just as intimidating as the piles of dice, homemade maps, and poorly-molded pewter figurines that they hauled out when showing us the ropes. Like most kids, I was both terrified of and fascinated with the unfamiliar -- which leads back to those comic book ads.

Feeling sweaty and like I was doing something decidedly perverse, one summer I decided to order a role-playing game catalog for fifty cents, off of a full-page ad for the Ninja Turtles RPG on the back cover of the latest issue of TMNT Adventures. I didn't know what I'd be getting, except that it was related to my beloved heroes in a halfshell. I mailed two quarters to Westland, Michigan, and tried to wave off the strange guilt that followed.

I can still remember the kind of paper used in the catalog that arrived weeks later from Palladium Books. A course, heavy stock, soon smudged with my fingerprints, offering no clear explanation as to how, exactly, the games it advertised could be played. It was more like Palladium was advertising novels, or comics, instead of playable games.

I can still remember the kind of paper used in the catalog that arrived weeks later from Palladium Books. A course, heavy stock, soon smudged with my fingerprints, offering no clear explanation as to how, exactly, the games it advertised could be played. It was more like Palladium was advertising novels, or comics, instead of playable games. Decades later, I would come to understand that the insular nature of Palladium products led equally to both their derision and allure in the gaming industry. Had I braved the awkwardness of learning D&D from my friends' older brothers, I would have experienced a game that was quite structured and user-friendly, with straightforward systems of dice-rolling and adventuring. Palladium, conversely, makes "games for gamers" -- that is, their game books create worlds and stories for experienced RPG players, and expect the players themselves to work out the details.

Which makes a lot of sense, in practice -- but not for a ten-year-old for whom Nintendo's TMNT III: The Manhattan Project was sophisticated interactive storytelling.

By adulthood, I had happened to acquire a dilapidated copy of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Other Strangeness, the main sourcebook for the TMNT RPG. It had shown up in a dollar bin at a thrift store, and proved even more impenetrable than I'd imagined it would be.

TMNT the RPG, I decided, looked more like work than fun. It looked like charts and graphs. It looked like tables and scoresheets. TMNT the RPG looked like math.

And without an RPG group, the learning curve on the game stopped me from further investigation.

It was only when I started thinking about the game for its sheer aesthetic and nostalgic value that I finally took the plunge in tracking down the holy grail of anthropomorphic nerdom, Mutants Down Under.

This image, culled from that old Palladium catalog, was the one that got my blood racing as a child. Mutants Down Under was an offshoot of a game called After the Bomb, which was in turn a sort of futuristic spinoff of the Ninja Turtles game itself. The TMNT were cool, but I knew them well. Even their scary black-and-white iterations weren't really a leap into the unknown.

But this. This. Punk kangaroos with uzis. Horrible man-eating plants, airships from Malaysia, and roaming militant water buffalo.

"A post-apocalyptic world of mutant animals."

Wha. Duh. Fuh.

In After the Bomb, mutants had gone global, and faced insurmountable dangers. It sounded terrifying, and fascinating.

The short paragraph describing the Mutants Down Under game contained every crazy thing I could possibly imagine. My ten-year-old self couldn't fathom it, and my thirty-year-old self couldn't process it.

But my thirty-year-old self could eBay it.